- Doctors & Departments

-

Conditions & Advice

- Overview

- Conditions and Symptoms

- Symptom Checker

- Parent Resources

- The Connection Journey

- Calm A Crying Baby

- Sports Articles

- Dosage Tables

- Baby Guide

-

Your Visit

- Overview

- Prepare for Your Visit

- Your Overnight Stay

- Send a Cheer Card

- Family and Patient Resources

- Patient Cost Estimate

- Insurance and Financial Resources

- Online Bill Pay

- Medical Records

- Policies and Procedures

- We Ask Because We Care

Click to find the locations nearest youFind locations by region

See all locations -

Community

- Overview

- Addressing the Youth Mental Health Crisis

- Calendar of Events

- Child Health Advocacy

- Community Health

- Community Partners

- Corporate Relations

- Global Health

- Patient Advocacy

- Patient Stories

- Pediatric Affiliations

- Support Children’s Colorado

- Specialty Outreach Clinics

Your Support Matters

Upcoming Events

Child Life 101

Wednesday, June 12, 2024Join us to learn about the work of a child life specialist, including...

-

Research & Innovation

- Overview

- Pediatric Clinical Trials

- Q: Pediatric Health Advances

- Discoveries and Milestones

- Training and Internships

- Academic Affiliation

- Investigator Resources

- Funding Opportunities

- Center For Innovation

- Support Our Research

- Research Areas

It starts with a Q:

For the latest cutting-edge research, innovative collaborations and remarkable discoveries in child health, read stories from across all our areas of study in Q: Advances and Answers in Pediatric Health.

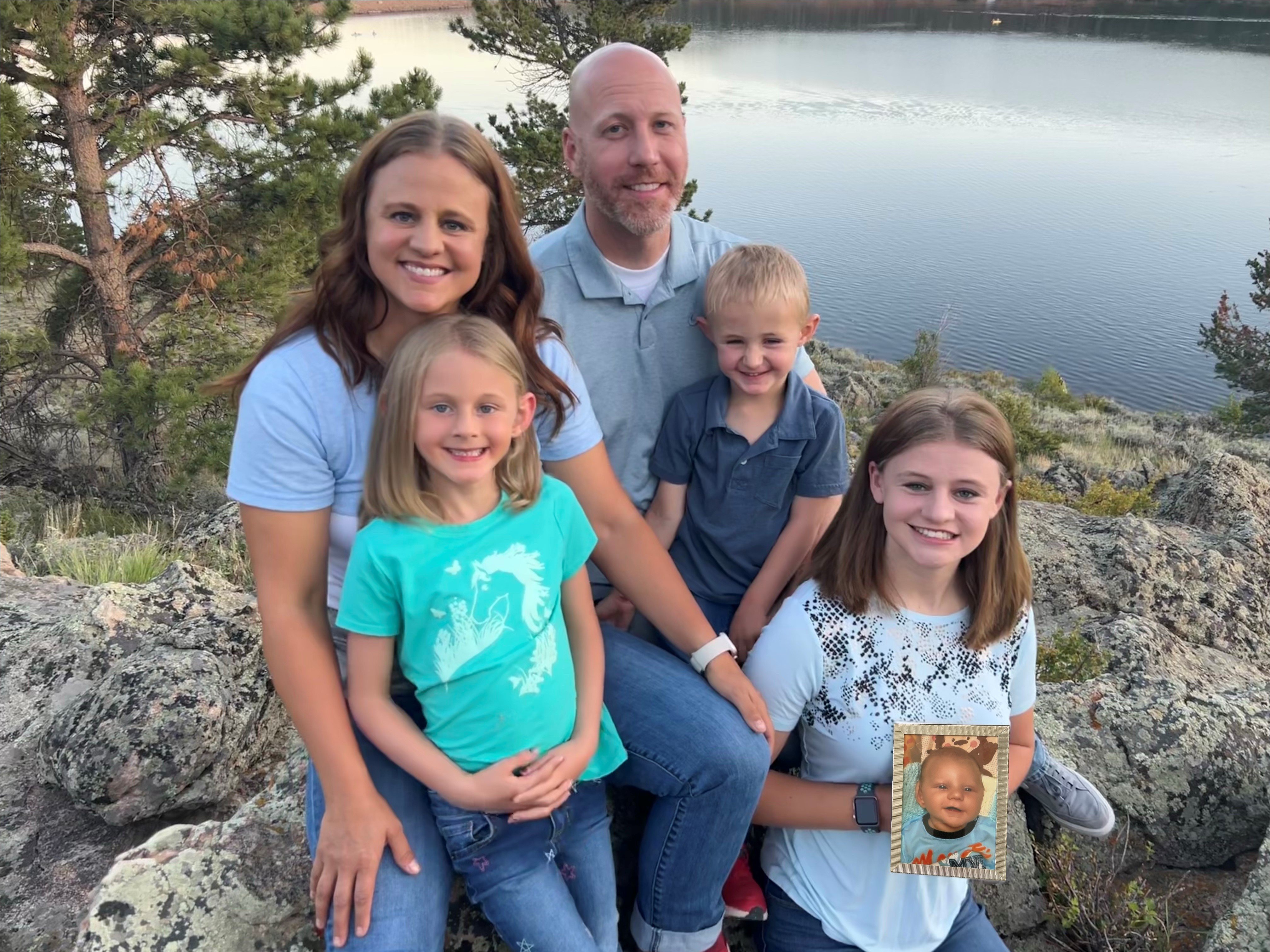

Grayson: How Genetic Testing Saved His Life

It’s rare to see the story of medical progress evolve within a single family. We don’t always see how research, innovation and brilliant providers impact individual kids. When we do get a peek, it’s literally lifesaving.

That’s the case for Grayson and his family.

They felt the joy and relief that doctors and researchers can provide when they’re willing to look through billions of pieces of genetic information. They also felt the profound sadness of having more medical questions than answers. Ultimately, their story and determination will help numerous children — some who aren’t even born yet.

The road to genetic testing

Grayson’s parents, Brittany and Robert, started genetic testing for him before he was born because they experienced the greatest loss parents can. At 3 and a half months old, they lost their son Drew to a genetic condition they didn’t even know he had.

He was a typical baby, but Brittany noticed he was sleeping more than normal. She took him to their pediatrician, who quickly sent her home with a diagnosis of ‘reflux.’ Drew began having seizures and after being admitted to the Intensive Care Unit in New York and undergoing an MRI, doctors found brain damage and high levels of homocysteine, an amino acid in the blood that helps create proteins. This issue can cause problems in brain development, strokes, blood clots and heart disease. Doctors tried to find out what caused this increase, but while fighting for answers, Drew passed.

“We still tried to figure out genetically what was wrong,” says Brittany. “We always imagined having a big family as my husband comes from a family of 10.”

In search of answers, Brittany and Robert underwent genetic testing that found inherited (passed down from parents) genetic variations in two different genes that the doctors in New York believed caused the issues Drew faced. Sadly, Drew had passed before doctors could collect DNA samples from him.

When Brittany became pregnant again, doctors referred her to Children’s Hospital Colorado – specifically to Peter Baker, MD, a biochemical geneticist and one of our metabolic specialists. As a recognized Rare Disease Center of Excellence by the National Organization for Rare Disorders (NORD), we have experts who have experience in caring for rare conditions, no matter how uncommon they are. Our specialists were concerned that the genetic information from Drew may not provide answers about Grayson’s health. They couldn’t be sure that Grayson would have the same condition, even if he carried the same changes. Our doctors suggested Brittany deliver at our Colorado Fetal Care Center to ensure she and baby Grayson would have the best care.

“The minute we sat down with Dr. Baker it was a completely different experience,” says Brittany. “Finally, someone listened to us, and they wanted to find out what was going on just as much as we did.”

A methionine synthase deficiency diagnosis from whole genome testing

Before birth, genetic testing of Grayson’s amniotic fluid showed he carried both genetic variants previously found in the family. Due to Brittany and Robert’s experience, and skepticism that the previous genetic findings in Drew were the real explanation for his problems, our doctors recommended that we monitor Grayson carefully and do more extensive testing when he was born.

“We knew the mutations were serious and the disorder could start causing damage very quickly, so the plan helped alleviate a lot of fears we had about missing any signs that he had the disorder,” says Brittany.

Hours after he was born, Shawn McCandless, MD, Chair of our Section of Genetics and Metabolism, Dr. Baker, and other providers saw Grayson and ordered his first blood test that showed his homocysteine level was extremely high — the same as Drew. Our team immediately sent an ultra-rapid whole genome test on Grayson to Rady Children’s Hospital — a genetic test that looks at all the genetic material, around three billion bits of information. The earlier genetic testing Drew had looked only at the exons of genes, which are easier to test, and only evaluated about three percent of the genome.

So, our experts worked with colleagues in San Diego to look deeper into the two genes. They found a second change in one of them — a missing piece of genetic information. That missing information is often difficult to find using traditional DNA sequencing methods, but the cutting-edge whole genome test can dig deeper. This missing genetic material fully explained the findings in both boys. Most importantly, it pointed to a specific treatment that might give Grayson a different outcome than Drew.

“We are really good at finding mutations in exons, but we found this in the introns, way in the middle of the gene where you don’t usually expect to find things,” says Dr. McCandless. “We can now understand how it was missed the first time.”

Drs. Baker and McCandless reached out to a colleague, David Rosenblatt, MDCM, at McGill University in Montreal, who is a top expert in these types of metabolic disorders. His laboratory functionally confirmed the methionine synthase deficiency diagnosis. Dr. Rosenblatt’s lab continues to use this information to help people like Grayson who need to better understand whether specific genetic changes are causing their metabolic condition.

“Not only did we get an answer for Grayson and his brother, but what we have learned will likely help many others,” says Dr. McCandless. “Our hospital is developing the tools to perform whole genome sequencing in our own Precision Diagnostics Laboratory.”

Brittany and Robert now had answers for what had taken Drew, but further, what could save Grayson.

Grayson has methionine synthase deficiency, also known as Cobalamin G disease, meaning he has low levels of an essential amino acid, methionine, which is critical for many important processes in the body, including making and regulating DNA. Left untreated, low methionine causes severe problems in brain development, while high homocysteine increases the tendency for strokes, blood clots, heart disease and seizures.

Using precision medicine to treat Grayson’s methionine synthase deficiency

We treated Grayson within the first few days of life with methionine, an essential amino acid. He’ll continue to take a special mix of vitamin B12 injections and other medication and undergo routine lab testing for the rest of his life. But now that his family has answers, Grayson is free to be a kid.

Finding the exact cause of Grayson's issues — and in turn — the right treatment to help him, is an example of precision medicine. This practice uses a child's genetic information, advanced diagnostic technology and a wealth of data to create personalized treatment for each child, when appropriate. Many of our teams have been practicing precision medicine for years and our Precision Medicine Institute works to advance our capabilities in this area so we can give more answers and hope to families like Grayson's.

“A lot of families didn't go through what we went through with Drew,” says Brittany. “As a community, we're grateful we have treatment at all.”

Since losing Drew and finding treatment for Grayson, Brittany has advocated to help other kids and families affected by this rare genetic disorder. She leads the Cobalamin steering committee for the Homocystinuria Network of America to provide support and resources for families and community members around the world, and she fundraises for research into these extremely rare conditions.

“Watching how bad this disease can get and now seeing how well our other son is doing, I can't not advocate,” says Brittany.

Thanks to our metabolic specialists and countless other providers, Grayson and so many other children can run and play. At 4, Grayson loves preschool and superheroes. He has a minor speech delay, takes daily medication and has routine treatment for a chronic illness, but he’s thriving.

“He’s the strongest kid we know,” says Brittany. “I will always tell other parents about Children’s Colorado for second opinions. We must make sure that kids all over the world are getting the correct treatment.”

720-777-0123

720-777-0123